Thanks to my good friend, Jim, I had the opportunity to attend the Performance Racing Industry Trade Show (PRI) this past December. For anyone passionate about motorsports, PRI is one of the most immersive racing industry events in the world. The show spans more than 1.1 million square feet and features everything from race cars and engines to simulators, data systems, and professional-grade tools used by teams across nearly every form of motorsports. Walking the PRI floor feels less like attending an event and more like stepping inside the business of racing itself.

What makes PRI especially exciting—and unique—is that it’s not open to the general public. This isn’t a fan expo or auto show. It’s a motorsports trade show built for teams, manufacturers, engineers, sponsors, and industry professionals. Instead of viewing cars behind ropes, you’re standing next to the people who design, build, test, and race them. Conversations happen openly, partnerships are formed, and ideas move quickly. For someone who has followed racing from the outside, being inside that environment offers rare access and a deeper understanding of how modern motorsports actually works.

With that kind of scale and access, PRI can be overwhelming if you don’t go in with a plan. So instead of trying to see everything, I focused on answering a question I’ve been asking myself for years:

Can a kid from a middle-income or low-income family realistically get into motorsports and make a living, starting with sim racing?

Motorsports has always carried a reputation as a pay-to-play sport. And honestly, that reputation is earned. Unlike stick-and-ball sports, there is no cheap, public entry point. You don’t just need talent—you need equipment, travel, coaching, seat time, and constant funding. For many families, the cost barrier alone ends the dream long before it ever has a chance to become real.

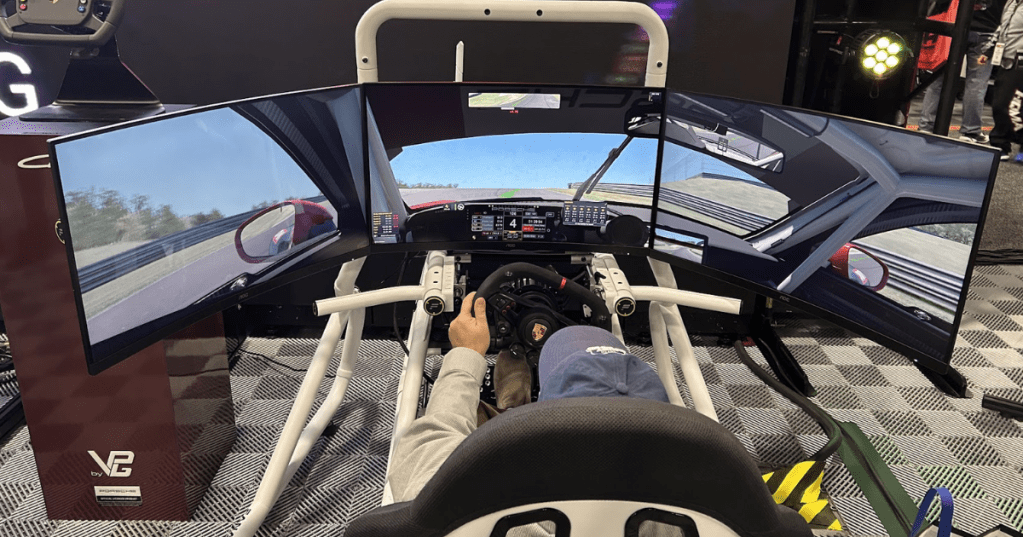

But walking the PRI floor, something stood out. Simulators weren’t tucked into corners as novelties. There was an entire section dedicated to sims. That made me stop and ask whether racing simulators are still “just games,” or whether they’re quietly becoming a legitimate on-ramp into professional motorsports.

The Traditional Motorsport Barrier

Most professional racing careers start young. Karting programs often begin before a child is ten years old, and the costs escalate quickly. Engines, tires, track fees, coaching, travel—by the time a driver reaches their teens, competitive programs can easily reach six figures per year.

Talent alone doesn’t carry you very far in that system. Without funding, sponsorship, or the right connections, many capable drivers simply run out of runway. That’s not because motorsports is unfair—it’s because racing is expensive, and someone has to pay for it.

For decades, this has limited the talent pool to families who could afford the gamble.

Sim racing challenges that structure—not by eliminating costs entirely, but by lowering the first and most critical barrier: access.

What Sim Racing Changes—and What It Doesn’t

At its core, sim racing dramatically reduces the cost of entry. A modest PC, a wheel and pedals, and a subscription to platforms like iRacing can put a driver into organized, competitive racing for a fraction of the cost of a single real-world race weekend.

It also removes geographic barriers. You don’t need to live near a track. You don’t need a trailer or a support crew. You just need time, discipline, and a reliable internet connection.

What sim racing doesn’t do is remove competition. At the top levels, sim racing is brutally competitive. Thousands of drivers fight for hundredths of a second, and success depends on racecraft, consistency, adaptability, and mental endurance—not just raw speed.

And importantly, sim racing does not replace real racing. There are no sustained G-forces, no heat, no fear factor, and no physical punishment. Teams know this. But they also know something else has changed.

How Realistic Sim Racing Has Become

Modern simulators are far more sophisticated than I realized.

High-end sim racers use direct-drive steering wheels that transmit detailed force feedback directly from the simulation’s physics model. Drivers can feel tire load building, the onset of understeer, rear-end instability under throttle, and even subtle surface changes. While the forces may be exaggerated, the information is accurate—and that’s what teams care about.

Braking realism has improved just as much. Load-cell and hydraulic pedals measure pressure instead of movement, forcing drivers to brake the way they would in a real car. This allows precise practice of threshold braking, trail braking, and brake modulation—skills that transfer directly to GT, endurance, and stock car racing.

Haptic feedback fills in some of the gaps left by missing G-forces. Vibration systems mounted to seats, pedals, and chassis can signal wheel lock, ABS activation, tire slip, and road texture. Drivers may not feel the cornering force, but they learn when grip is lost—and timing is critical in real cars.

Many professional teams actually prefer static simulator rigs over full motion platforms. Motion can enhance immersion, but poorly tuned systems can be misleading. What matters most is consistency, repeatability, and data—and simulators excel at all three.

Add in laser-scanned tracks, accurate car models, and detailed telemetry, and sim racing becomes something far closer to a training environment than a video game.

From Pixels to Paddock: Real Examples

This isn’t theoretical anymore. Drivers have already made the jump.

Jann Mardenborough famously transitioned from sim racing through Nissan’s GT Academy into professional GT and endurance racing. His success forced teams to take simulators seriously as talent identifiers.

In open-wheel racing, Igor Fraga used success in the F1 Esports Series as a springboard into real-world Formula competition, supported by manufacturer development programs.

In the U.S., William Byron often credits sim racing as part of his early development before climbing through late models and ultimately reaching NASCAR’s top level. While funding still played a role, sim racing helped sharpen his racecraft and visibility early on.

These drivers aren’t proof that sim racing guarantees success—but they are proof that teams now recognize sim performance as meaningful.

What Teams Are Actually Watching

Teams aren’t just looking at who wins sim championships. They’re looking deeper.

Consistency, clean racecraft, adaptability to different cars, decision-making in traffic, and the quality of driver feedback all matter. Sim platforms generate enormous amounts of data—lap traces, braking points, throttle application, incident rates—that allow teams to compare drivers objectively before ever putting them in a real car.

At PRI, simulators weren’t positioned as replacements for real testing. They were positioned as filters—ways to narrow thousands of hopefuls down to a manageable few.

A Door, Not a Guarantee

After walking PRI and seeing how deeply simulators are embedded in modern motorsports, one thing became clear:

Sim racing is not a golden ticket. It doesn’t replace seat time. It doesn’t eliminate the need for funding. And it doesn’t guarantee a career. But it can open a door that used to be closed.

For kids from middle or low-income families, that matters. It means skill can surface before money decides the outcome—and in motorsports, that’s a meaningful shift.

The harder question is what happens after a driver gets noticed. That’s where the real bottleneck begins.

In Part 2, we’ll look at how sim racers turn virtual success into real seat time, what still holds them back, and whether this pathway is expanding—or quietly narrowing—as more people try to take it.

Leave a comment